- Play video

The Shell Record, 2021

ERC-721 token, PNG + MP4

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of Gazelli Art House Ltd.

Copyright The Artist

About The Artwork

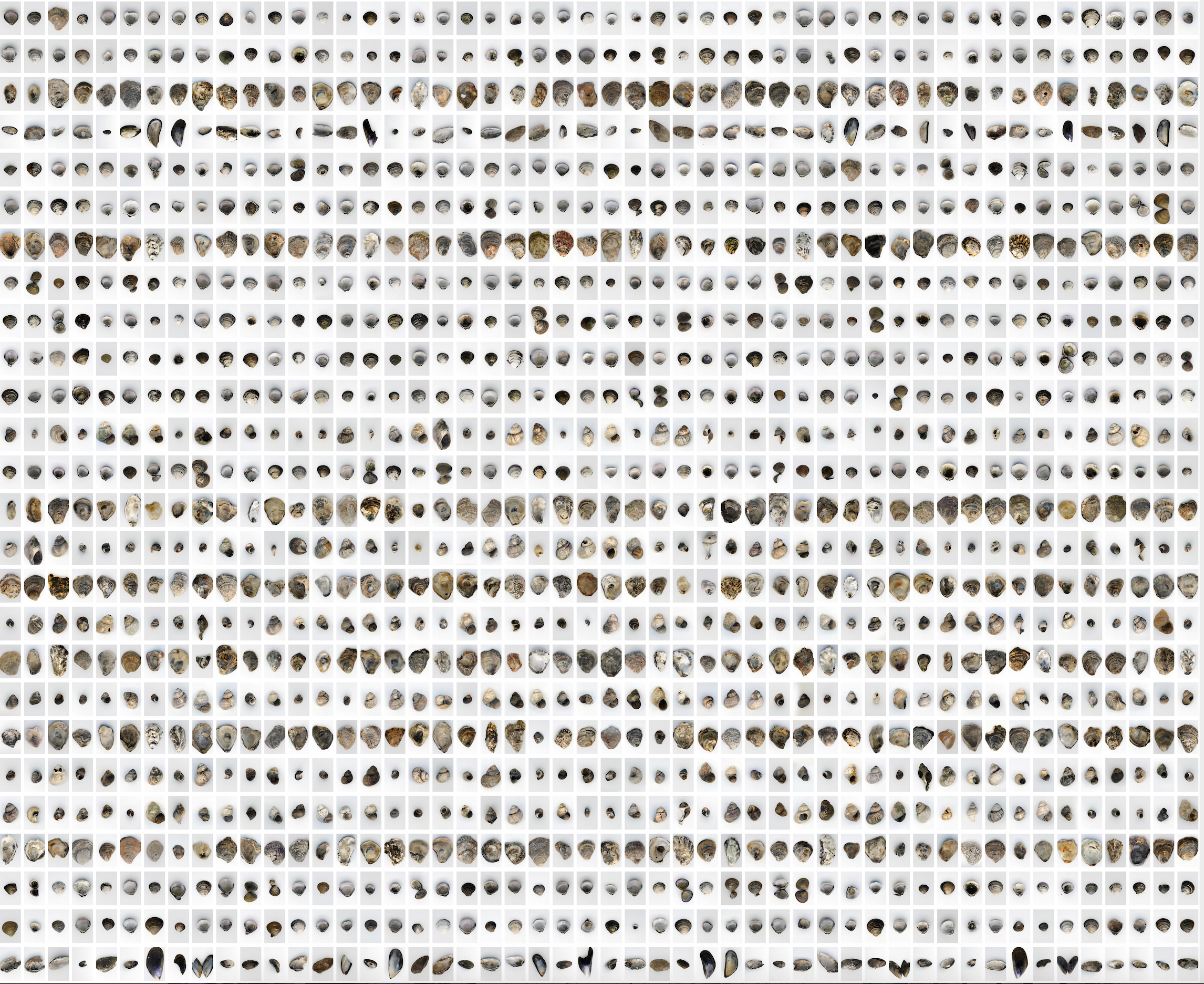

The Shell Record is a project that is made up of an image of the hundreds of shells that I collected from the foreshore of the Thames organised into a grid and used as a training set, and a moving image piece that resulted from training a model on them. The piece was created with the intention of being sold as an ERC-721 token as part of the Sotheby’s Digitally Native sale in 2021 and ideas around ownership, trade and value are threaded through it, conceptually and practically.

At the time of the sale, there was growing interest in the fine art market for ERC-721 tokens after several large sales by traditional auction houses. The space was showing increased commercialisation with works bought and traded as if they were commodities, while at the same time there was increased institutional interest in cryptocurrencies as a class: all of this was reminiscent of speculative bubbles.

The work references this context as well as the broader ERC-721 token space. The contract is written in such a way that as the piece gets sold it will change – the image of the dataset becomes larger with more images of shells included, the moving image piece becomes longer and slows down. The subject matter of shells is deliberate: they have been used as stores of value and tokens of ritual significance for thousands of years. ‘Store of value’ is a term used by economists to describe how certain objects - usually currency, property, financial assets or precious metals - can be held or traded over a long period of time, without losing value.

Traditionally it has not been applied to organic objects which decay and decompose over periods of time, and it is arguable as to whether it can be applied to cryptocurrencies which are subject to volatile price swings and speculation, something that has been explored in the essay “Shelling Out". Before the rise of modern financial systems, shells were used as money on nearly every continent on earth, and thought to have been used as such for at least 9,000 years.

As cryptocurrency now aims to overturn the paradigm of fiat money, much like how metallic coinage overturned the paradigm of shell money, it felt appropriate to reach back to this ancient form of value and bring it into the future. This shadow/echo of fiat money is embedded in the piece, as it is so specific to London: the shells come from stretches of river that are in the heart of one of the centres of global financial capitalism.

Shells were also the subject of their own speculative mania, much like tulips. European collectors spent enormous sums of money on rare shells in the 18th and 19th centuries. Shells that were collected were often placed in cabinets of curiosities, a space where objects were selected because of their value and aesthetics and brought together through the act of collecting. There does feel to be an echo of this in how NFTs are brought together on certain sites, grouped by collectors to showcase a different type of status.

Making this work took several months finding and collecting shells from different locations along the Thames River, which is one of the largest open archaeological sites in the world. The act of scavenging for objects (including shells) along the Thames, otherwise known as mudlarking, dates back to the 18th century. It is now a highly regulated activity and illegal to remove anything from the bank of the river Thames without a permit from the Port of London Authority, who own the foreshore to the high water mark. Ownership of the river has passed back and forth from different bodies and institutions (Environmental Agency, British Waterways, The Crown, The City of London Corporation) and been the subject of multiple acts of parliaments. This ownership of something that is freely enjoyed is reminiscent of NFT ownership of something that is freely on the internet. Also the absurdity of legal structures onto something naturally occurring like shells. When mudlarking It is easy to see how the history of the river has changed, even through something as simple as shells. There are a multitude of oyster shells, which no longer live in the Thames as large amounts of pollution destroyed their population but were prevalent in Victorian, Georgian and even Roman times. Some even have the stamp of the farmers who cultivated them. It is possible to find shells that clearly do not originate from the Thames but are testaments to the history of trade - cowrie shells that I found in Bermondsey that must have arrived back when it was an active wharf. There are new types of shells that have been brought in by globalisation and new shipping routes. Scientists see that shells that have been in the river since the Ice Age are now “rare, outcompeted & replaced by a massive influx of invasive species” & think that these new species will eventually become fossil time-markers for the Anthropocene. I’m always interested in taking a single object and unpacking it, and this piece was a way to start to understand the change and flux in the human and natural worlds.

(Text taken from forthcoming book)

About Anna Ridler

Anna Ridler (B. 1985) is an artist and researcher who works with information and data. She is interested in systems of knowledge, with a desire to know and to make this process of knowing available. She works with new technologies, exploring how they are created in order to better understand society and the world. Her process often involves working with collections of information or data, particularly self-generated data sets, to create new and unusual narratives in a variety of mediums and how new technologies, such as machine learning, can be used to translate them to an audience.

She holds an MA in Information Experience Design from the Royal College of Art and a BA in English Literature and Language from Oxford University along with fellowships at the Creative Computing Institute at University of the Arts London (UAL), Ars Electronica, Edinburgh University and the Delfina Foundation.. Her work has been exhibited at cultural institutions worldwide including the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tate Modern, the Barbican Centre, Centre Pompidou, HeK Basel, the ZKM Karlsruhe, Ars Electronica, Sheffield Documentary Festival and the Leverhulme Centre for Future Intelligence. She was a European Union EMAP fellow and the winner of the 2018-2019 DARE Art Prize. Ridler has received commissions by Salford University, the Photographers Gallery, Opera North, Live Cinema UK and Impakt Festival. She was listed as one of the nine “pioneering artists” exploring AI’s creative potential by Artnet and received an honorary mention in the 2019 Ars Electronica Golden Nica award for the category AI & Life Art. She was nominated for a “Beazley Designs of the Year” award in 2019 by the Design Museum for her work on datasets and categorisation.

Ridler lives and works in London.